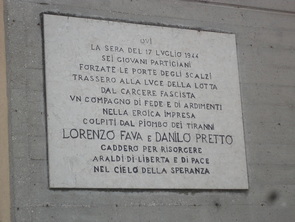

Convegno, Gran Guardia Convegno, Gran Guardia Undeterred by my previous encounter with historical commemoration in Italy (see Una Ragazza in Guerra), I recently went along to another event to honour heroes of Verona’s resistance movement. The convention was held in the plush surroundings of Verona’s Gran Guardia and marked the 70th anniversary of the death of the two ‘heroes of the Scalzi’, Lorenzo Fava and Danilo Preto. In attendance were various political dignitaries, including Stefano Casali, the charismatic vice-mayor of Verona. Despite having a different political outlook to the protagonists in this story, he spoke of the importance of their contribution to democracy. Another speaker explained that as a child he had attended Scuola Media Lorenzo Fava, without at the time appreciating the significance of the school’s name. He emphasised the importance of passing on these stories to our young people. Avid readers may remember that during the Second World War The Scalzi was a prison in Verona in which a number of anti-fascists, as well as Mussolini’s son-in-law Count Galeazzo Ciano, were detained (see A Place of Execution).  The young heroes of the Scalzi, Danilo Preto and Lorenzo Fava The young heroes of the Scalzi, Danilo Preto and Lorenzo Fava Preto, the son of railway worker, was a 21-year old typewriter repairman. Fava, 25 years old, was a law student at the University of Padova with a passion for literature. He had already seen combat, earning the Croce di Guerra for leading a platoon of riflemen as they successfully conquered an enemy position in Montenegro. He had also committed various acts of sabotage, including the destruction of the Italian-German reading room in via Mazzini, accomplished by placing on the shelves a book by the German writer and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Hidden inside the book was a bomb!  A surviving wall of the Scalzi prison A surviving wall of the Scalzi prison On 17 July 1944, Fava and Preto, alongside fellow Gapisti (Gruppi di Azione Patriottica) Emilio ‘Bernardino’ Moretto, Berto Zampieri, Vittorio Ugolini and Aldo Petacchi, launched an audacious attack on the Scalzi. Their mission: to liberate prominent trade union leader Giovanni Roveda. Roveda was already a national symbol of antifascism and a central figure in the mobilization of Italian workers against the fascist regime. In February 1928 he had been convicted and sentenced to twenty years and four months in prison. He served 11 years and was released on amnesty. However, in April 1937 he was sent into internal exile in Ponza for being insufficiently repentant of his crimes. He was then transferred to Ventotene, a remote island of the coast of Napoli. In March 1943, taking advantage of a permit to visit his sick wife, he escaped.  A plaque in via Scalzi that records the events of 17 July 1944 A plaque in via Scalzi that records the events of 17 July 1944 At first he hid in Biella, in north western Italy, then in July 1943, after the collapse of the Mussolini regime, he moved to Rome, from where he represented the labour movement in government. After the armistice of 8 September and the re-establishment by the Germans of the Mussolini government, Roveda took refuge in a seminary. In December 1943 he was re-arrested by the Banda Koch, a notorious gang of partisan hunters. He was then transferred to the Scalzi prison in Verona. At 18.20 on the 17 July 1944, the Gappisti, including Fava and Preto, enter the prison, cut the telephone lines, and locate Roveda. As they are escaping, a fierce shootout begins. They make it to the getaway car, but it won’t start. Preto is hit and gravely wounded. His comrades try desperately to push-start the vehicle. Fava and Moretto, who get out to push, are also hit, as is the trade unionist Roveda. With a skid of the flat back tyre, the car finally starts. Not far from the prison, Zampieri, Ugolini, Petacche and Roveda abandon the car in search of a safe house. Morretto, the driver (three bullet wounds), Preto (in agony) and Fava (unconscious) finally ditch the vehicle at Porto San Pancrazio. It's curfew time. They search in vain for help. Preto and Fava are seized by the fascist police. Fava, having destroyed his documents to avoid recognition, is taken to the military barracks Casermette di Montorio to be tortured by the SS. In response to threats that his parents will be killed, Fava ironically replies that he also has a granny aged 92. For two days he is deprived of water. His mother, who seeks news for him at the Palazzo dell’Ina (see in this building…), is told that he has been deported to Germany. On 23 August 1944, he is secretly taken to the firing range at Forte Procolo where he is shot in the back. His body is taken to the Cimitero Monumentale. It is a year before his family finally discover his fate. The trade unionist Giovanni Roveda became the first mayor of liberated Torino. He died in 1962 of phlebitis, caused by the bullet that had been in his body since his breakout from prison in 1944. He remains a revered and respected political figure. Fava and Preto, the heroes of the Scalzi, were posthumously awarded the Medaglia d’oro for military valour. The bodies of the two young comrades lie together in Verona’s Cimitero Monumentale. Update:

With thanks to some detailed directions from the helpful staff at the Istituto Veronese per la storia della resistenza e dell'etå contemporanea, I was finally able to locate the gravestone of Lorenzo Fava and Danilo Preto. See below. |

AboutRichard Hough writes about history, football, wine, whisky, culture + travel and is currently working on a trilogy about wartime Verona.

|