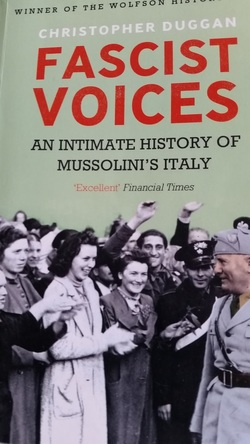

Fascist Voices by Christopher Duggan

|

Christopher Duggan's Fascist Voices, An Intimate History of Mussolini's Italy, is a detailed and troubling account of a dark period in Italian history.

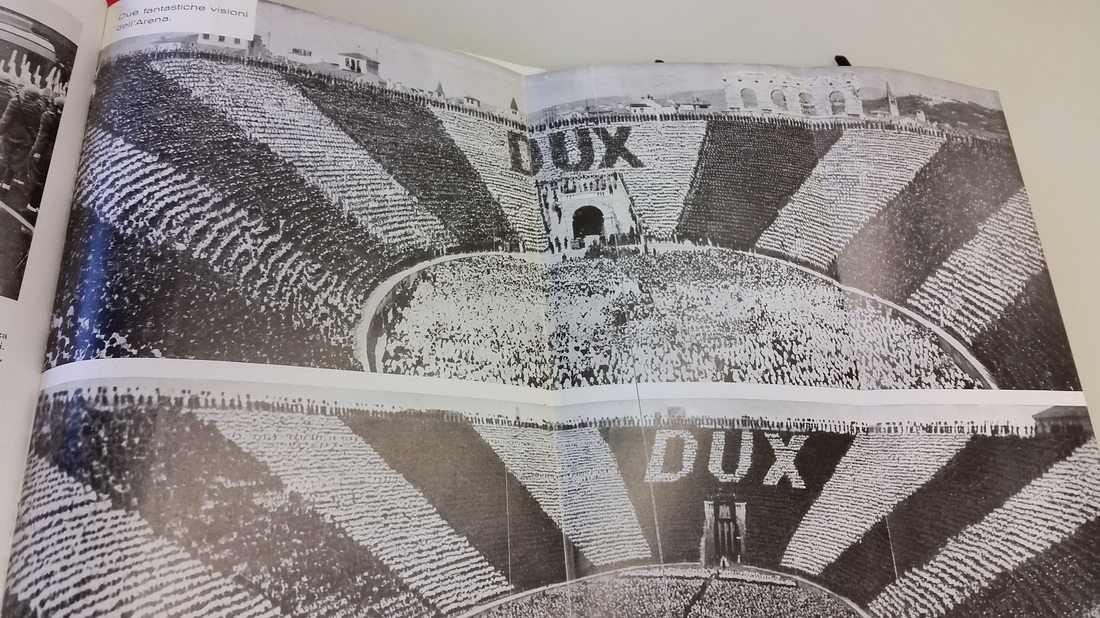

Using first hand accounts, including letters and diaries written by ordinary Italian's, Duggan explores the disturbing cult of Mussolini, revealing the extent to which ordinary people were utterly seduced by the Italian dictator and his ideology. In the 1930s, Mussolini received around 1,500 letters a day, and it is these letters that form the backbone of Duggan's analysis. Duggan is Professor of Modern Italian History at the University of Reading and, as you might expect, his analysis is detailed, methodical and dispassionate. Despite this, the picture that emerges, of a population that has collectively lost control of its critical senses, is deeply disturbing. Of course, there are some mitigating factors that perhaps explain, if not justify, Italy's enthusiasm for fascism, including the extraordinary economic and political circumstances of the time (Duggan notes that average per capita income in Italy in 1934 was almost half that of Britain), and the extent to which the Italian people were indoctrinated by the intense fascist propaganda, control and intimidation. Duggan observes that this control and repression became particularly assiduous in the months immediately before the Second World War (in response to mounting popular disquiet with the direction of Italian foreign policy). While fascism seems to have deprived a generation of Italians of the ability to think, there were, of course those Italians who opposed fascism, increasingly so after the disastrous alliance with Germany in 1943. But for me, these mitigating factors do not fully explain quite how so many Italians were so willing to devote themselves so unquestioningly to such a tyrannical leader and such a flawed ideology. Of course the same question might well be asked about Nazi German, Soviet Russia and North Korea, in fact, anywhere where a one-party, totalitarian state exists. While it might be reassuring to imagine that the Italian people were victims of fascism rather than willing collaborators, one only has to look at pictures, like those below taken during Mussolini's 1938 visit to Verona, to understand the enthusiastic support that fascism in general and Mussolini in particular enjoyed. Of course, such events were scrupiously stage managed and controlled. But, the toe-curlingly sycophantic letters and the "intensity of people's feelings towards Mussolini" that Duggan has unearthed show that, for many, fascism and in particular its charismatic leader were adored. As Duggan points out, however, many were drawn to fascism not for ideological reasons, but out of economic self-interest and, as any A-Level student of Modern History will be able to tell you, the cause of fascism was hugely assisted by the ineptitude of its enemies. It is one of Duggan's ironic observations that, while fascism was thought by many to provide the best guarantee of law and order, it relied upon violence itself to do so. Duggan also notes more recent utterances by figures like Silvio Berlusconi, who contend that while Mussolini might have made some regrettable errors (such as allying with the Nazis and passing racial laws), his regime was generally benign. Duggan also reproduces a representative selection of the messages left in the registers placed in front of Mussolini's tomb. Alarmingly, almost all of them have done so in a spirit of admiration for the former Duce. As an aside, one prominent figure from this period who has always intrigued me is the playwright, poet, novelist, war hero, womaniser, nationalist and prototype fascist, Gabriele D'Annunzio. His villa remains intact on the banks of Lake Garda and it has long been my intention to pay a visit. In a tantalising vignette, Duggan explains how the poet was seriously hurt when he lost his balance and fell from a window of his lakeside villa while fondling the sister of his mistress while high on cocaine. |