|

Exploring Fontanellato, its notorious POW camp and a remarkable escape

Deciding to escape from Verona for the day, our objective is Fontanellato, a small town in north western Italy, an ambitious (with two restless children) two hour drive from Verona, approximately 20 kilometres west of Parma.

Fontanellato is home to the Santuario Basilica della Beata Vergine del Santo Rosario (above), a striking dominican sanctuary that commemorates a succession of miracles dating back to 1628. The monastery is still active and monastic chanting provides an haunting backdrop to our whistle stop tour of the convent. The Rocca Sanvitale (below) is a fortress-residence located in the centre of Fontanellato. Its origins can be traced back to the 13th century. Until as recently as the 1930s it was home to the descendants of the first Count of Sanvitale.

The fortress is beautifully maintained, as are the surrounding bars and shops, which have a uniform typescript and coordinated pastel shades, creating an atmosphere that is both clean and modern and respectful of the past. But it wasn't for the monastery or even the medieval fortress that we had made the journey to Fontanellato. In 1943, Fontanellato was a prison town, home to 600 allied prisoners of war (POWs).  The former POW camp at Fontanellato The former POW camp at Fontanellato

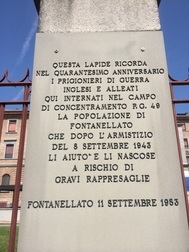

The POWs occupied a four storey building next to the monastery - PG49 (see above). The prison, which was originally designed to be an orphanage, is now a hospital. A plaque on the perimeter fence (see below) commemorates its wartime inhabitants and the local people who, despite the grave risk of reprisals helped them escape.

PG49 was a relatively tranquil place to see out the war. Compared to the conditions endured by POWs in Japan and Germany, the regime at PG49 was relatively safe and secure. Wine was served with lunch and POWs were issued with a daily ration of Vermouth! According to some accounts, it was more like an Oxbridge common room than a wartime detention centre for enemy combatants. The peace and tranquility of the prison, though, couldn't last forever.

In the summer of 1943, there were approximately 80,000 British POWs in Italian prison camps. On 7 June 1943, the British intelligence agency responsible for helping captured allied personnel (MI9) issued Order P/W 87190. In the event of an allied invasion of Italy, this order required all allied prisoners in Italy to "stay put" (rather than attempt to escape). As a consequence, when the armistice was subsequently signed, 50,000 allied prisoners were immediately recaptured by the Germans and shipped north to Germany and Poland, where many are thought to have perished. Some of those who disobeyed the order managed to escape - 5000 north through the Alps to neutral Switzerland and 6,500 south, to the slowly advancing Allied line. Many prisoners, however, remain unaccounted for.

At about 7.30pm on 8 September 1943, news of the armistice between Britain and Italy began to spread through camp PG49. By midday the following morning the detainees had filed past an impromptu Italian guard of honour and through a hole in the wire that the Italian camp commandant had ordered be cut (an act of defiance that would see him spend the rest of the war doing hard labour in a German concentration camp).

But, the escapees had grown used to the routine and relative safety of prison life. Unarmed and out of condition, they stepped out of prison and into the eye of the storm that was now engulfing northern Italy. A number of detainees of PG49 have written about their experiences. These include the famous travel writer Eric Newby. He escaped from PG49 with the help of a local girl called Wanda. After he fled the prison, Wanda and her father hid Newby from the Germans and then helped him to reach the mountains. Despite their brave efforts, Newby was recaptured in January 1944 and sent to a prison camp in Germany where he spent the rest of the war. After the war he returned to Italy to find and reward Italian partisans who had helped British soldiers escape. He found Wanda. They were married in Florence in 1946. Newby wrote about his wartime experiences in the book Love and War in the Apennines. He died on 20 October 2006.

Another detainee was Major Richard Carver, who had been captured in the Western Desert on 7 November 1942. Amongst the last to leave PG49, he made his way south with a pipe smoking colonel known as The Gloomy Dean. Ill-equipped for their journey through the mountains in the brutal Italian winter, with the help of many local contadini, Carver somehow made it through German occupied northern Italy and finally walked into American headquarters on the outskirts of Atessa, where he asked to see his stepfather.

Carver's stepfather was Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery, hero of El Alamein and commander of the Allied campaign in Italy. Carver flew back to Prestick Airport on 12 December 1943. His diary entry for that day reads: "Home again after 6 years!". Richard Carver died on 24 July 2007 aged 93. His incredible story is told by his son Tom Carver, the former BBC foreign correspondent, in the wonderfully written "Where the hell have you been? Monty, Italy and one man's incredible escape", published in 2009.

Dan Billany was a teacher and author. He joined the army in October 1940 and by July the next year was Second Lieutenant in the East Yorkshire Regiment. In February 1942 he was posted to North Africa, where his platoon was over-run by Rommel's tanks. He was captured and handed over to the Italians. He was initially held at Camp 66, north of Naples, where he met David Dowie, another English POW.

Dowie and Billany were then transferred to Camp 17 at Rezzanello, where Billany completed The Trap, a fictionalised account of his life. During this time Dan's friendship with David intensified but, after expressing his true feelings for him, he was shunned by Dan. However, their friendship resumed after Dan wrote David a poem to explain his feelings. At the beginning of April 1943 they were moved to Fontanellato, where they began to collaborate on a novel based on their prison life, The Cage.

After escaping from PG49, the two friends stayed together. As with other escapees, they were helped by the local population. They stayed with the Meletti family on a farm on the outskirts of Soragna, five miles north of Fontanellato for a few weeks during which time they finished The Cage. They then began to make their way over the Apennines towards the Allied forces, leaving the exercise books containing the manuscripts with Dino Meletti, who promised to post them to Britain after the war. By November Dowie and Billany had made it as far as Capistrello, 70 miles from the Allied line. In March 1946, Dan's thirteen exercise books arrived at the Billany home in Yeovil, Somerset. They became bestsellers and were translated into many languages. Neither Dan nor David made it back to England. They are thought to have perished somewhere in the Apennines. Dan Billany's story is told in the biography Dan Billany Hull's Lost Hero by Valerie A Reeves and Valerie Showan.

Fontanellato is a remarkable place to visit. Not just for its ancient monastery and medieval fortress, but for the remarkable stories of the prisoners of war who, for a time, were imprisoned here and who, with the help and bravery of so many local inhabitants, sought to escape from the yoke of fascism.

|

AboutRichard Hough writes about history, football, wine, whisky, culture + travel and is currently working on a trilogy about wartime Verona.

|