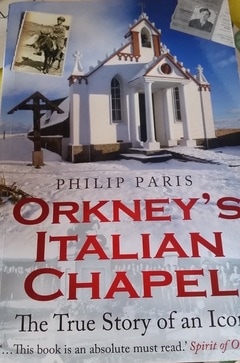

Orkney's Italian Chapel by Philip Paris

From wartime Orkney, Philip Paris tells the remarkable true story behind the construction of a quite unique place of worship.

Particularly striking is the fact that Paris stumbled upon the story quite by chance, while on honeymoon on the island in 2005.

Despite knowing nothing about the history of the chapel, other than that it had been built by Italian POWs during the Second World War, Paris and his new wife are deeply moved by their visit. Not everyone's idea of a romantic honeymoon, they then spend a rainy afternoon raking through the archives of the Kirkwall public library to learn more. In fact, the happy couple will spend the next 4 years researching the incredible story of the Orkney Chapel.

They track down ex-POWs and descendants of those who created the chapel, as well as prison guards and islanders who were around at the time.

Brimming with previously unpublished correspondence and detailed colour photographs, Paris presents a compelling, rich and compassionate account of Orkney's Italian POWs, conveying how they "overcame despair and loneliness to create a monument to the ability of the human spirit to rise above extreme hardship and hurt".

To understand what hundreds of Italian POWs were doing on Lamb Holm, a small uninhabited island that forms part of the remote Orkney Islands, an archipelago 10 miles north of the Scottish mainland, you really have to understand the geography of the region. Paris doesn't disappoint and provides a map of the Islands, as well as a more detailed illustration of the Scapa Flow, which was the main British naval base during the Second World War.

With easy access to the North Sea and the Atlantic, Scapa Flow had for centuries been a safe haven for mariners. The islands of the Flow form a natural barrier and these had been supplemented by a series of booms, anti-submarine nets and sunken 'blockships'. Unfortunately there were some gaps in the defences and, on 14 October 1939, HMS Royal Oak, at anchor in the Flow, was struck by 3 German torpedoes. Over 800 men lost their lives, including 126 boy sailors.

Following the loss of the Royal Oak an ambitious project of civil engineering was initiated to make the Flow more secure. Construction of the barriers, which became known as the Churchill Barriers, required manpower, a commodity that the remote Scottish island simply did not have. This is where the Italian POWs came in.

The Italian prisoners who were drafted in to construct the Churchill Barriers had been captured in North Africa after months of 'cat and mouse' fighting between Montgomery and Rommel. From the dessert theatre, they arrived on the barren Scottish island in the winter of 1942. They had been individually selected for their abilities and skills and had been vetted to filter out any possible fascist sympathisers.

Amongst those transferred to Orkney were artists and skilled craftsmen, including Domenico Chiocchetti, Giuseppe Palumbi, Domenico Buttapasta and Giovanni Pennisi, as well as stonemasons, blacksmiths, electricians and carpenters.

The inspiration behind the creation of the chapel was an Italian priest called Gioacchino Giacobazzi (Padre Giacomo), who hoped to raise the morale of the prisoners by providing a little church where they could congregate. With some difficulty, he persuaded the camp authorities to allow him to convert two wrought iron Nissen huts into a chapel. Apart from cement, they had virtually no building materials and little money to fund the project.

Somehow supplies, including poster paints, were obtained, and with these Chiocchetti created his masterpiece - a stunning altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child, based on a small religious card he had carried with him throughout the war.

By the summer of 1944, the Churchill Barriers had finally been completed. It is thought that the Italian's left the island around about this time. Many left behind friends they had made on the island during their long period of captivity. They also left behind their chapel, hopeful but not certain that it would survive after they left.

In 1992, eight ex-POWs returned to Orkney as honoured guests. Most had assumed that the Chapel had been destroyed in the intervening years. They were astonished to discover that it still stood, fragile but immortal.

Whilst there is no shortage of published accounts of wartime prison breakouts, the Italian POWs on the Orkney Islands were engaged in a completely different form of escapism. One of the joys of the book is that it tells not only the story of the chapel and of those who constructed it, but also the incredible journey of discovery by the author himself, as he learns more about the chapel and gets to know the families and decedents of those who built it. As he observes in his introduction, the real beauty of the chapel is how it connects people - "those from the past, those of varying beliefs and religions, people with different nationalities and languages. It had helped to make enemies into friends and now it was reaching out to us".

Particularly striking is the fact that Paris stumbled upon the story quite by chance, while on honeymoon on the island in 2005.

Despite knowing nothing about the history of the chapel, other than that it had been built by Italian POWs during the Second World War, Paris and his new wife are deeply moved by their visit. Not everyone's idea of a romantic honeymoon, they then spend a rainy afternoon raking through the archives of the Kirkwall public library to learn more. In fact, the happy couple will spend the next 4 years researching the incredible story of the Orkney Chapel.

They track down ex-POWs and descendants of those who created the chapel, as well as prison guards and islanders who were around at the time.

Brimming with previously unpublished correspondence and detailed colour photographs, Paris presents a compelling, rich and compassionate account of Orkney's Italian POWs, conveying how they "overcame despair and loneliness to create a monument to the ability of the human spirit to rise above extreme hardship and hurt".

To understand what hundreds of Italian POWs were doing on Lamb Holm, a small uninhabited island that forms part of the remote Orkney Islands, an archipelago 10 miles north of the Scottish mainland, you really have to understand the geography of the region. Paris doesn't disappoint and provides a map of the Islands, as well as a more detailed illustration of the Scapa Flow, which was the main British naval base during the Second World War.

With easy access to the North Sea and the Atlantic, Scapa Flow had for centuries been a safe haven for mariners. The islands of the Flow form a natural barrier and these had been supplemented by a series of booms, anti-submarine nets and sunken 'blockships'. Unfortunately there were some gaps in the defences and, on 14 October 1939, HMS Royal Oak, at anchor in the Flow, was struck by 3 German torpedoes. Over 800 men lost their lives, including 126 boy sailors.

Following the loss of the Royal Oak an ambitious project of civil engineering was initiated to make the Flow more secure. Construction of the barriers, which became known as the Churchill Barriers, required manpower, a commodity that the remote Scottish island simply did not have. This is where the Italian POWs came in.

The Italian prisoners who were drafted in to construct the Churchill Barriers had been captured in North Africa after months of 'cat and mouse' fighting between Montgomery and Rommel. From the dessert theatre, they arrived on the barren Scottish island in the winter of 1942. They had been individually selected for their abilities and skills and had been vetted to filter out any possible fascist sympathisers.

Amongst those transferred to Orkney were artists and skilled craftsmen, including Domenico Chiocchetti, Giuseppe Palumbi, Domenico Buttapasta and Giovanni Pennisi, as well as stonemasons, blacksmiths, electricians and carpenters.

The inspiration behind the creation of the chapel was an Italian priest called Gioacchino Giacobazzi (Padre Giacomo), who hoped to raise the morale of the prisoners by providing a little church where they could congregate. With some difficulty, he persuaded the camp authorities to allow him to convert two wrought iron Nissen huts into a chapel. Apart from cement, they had virtually no building materials and little money to fund the project.

Somehow supplies, including poster paints, were obtained, and with these Chiocchetti created his masterpiece - a stunning altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child, based on a small religious card he had carried with him throughout the war.

By the summer of 1944, the Churchill Barriers had finally been completed. It is thought that the Italian's left the island around about this time. Many left behind friends they had made on the island during their long period of captivity. They also left behind their chapel, hopeful but not certain that it would survive after they left.

In 1992, eight ex-POWs returned to Orkney as honoured guests. Most had assumed that the Chapel had been destroyed in the intervening years. They were astonished to discover that it still stood, fragile but immortal.

Whilst there is no shortage of published accounts of wartime prison breakouts, the Italian POWs on the Orkney Islands were engaged in a completely different form of escapism. One of the joys of the book is that it tells not only the story of the chapel and of those who constructed it, but also the incredible journey of discovery by the author himself, as he learns more about the chapel and gets to know the families and decedents of those who built it. As he observes in his introduction, the real beauty of the chapel is how it connects people - "those from the past, those of varying beliefs and religions, people with different nationalities and languages. It had helped to make enemies into friends and now it was reaching out to us".